“The King [held] a large meeting, and very deep consultation with his council, about this land; how it was occupied, and by what sort of men. Then sent he his men over all England into each shire; commissioning them to find out… what, or how much, each man had, who was an occupier of land in England, either in land or in stock, and how much money it were worth.”

So speaks the Ango-Saxon Chronicle on the compilation of Domesday Book by William the Conqueror – the greatest swag-list ever created. Having seized all England for the Crown after the Conquest, the king was in his counting-house, counting out all his money.

It’s unusual that what is essentially a government tax assessment should still be remembered by the bulk of the population a thousand years after it was carried out. But then, Domesday is unusual. It was an unprecedented piece of documentation, unparalleled in Europe at the time, and to this day remains a legal document that is still valid as evidence of title to land.

Curiously, however, people have forgotten about England’s Modern Domesdays. At least four times in the past two centuries, governments have carried out comprehensive appraisals of who owns England. The record books, maps and valuation tables that make up these surveys are far more relevant to who currently owns this island than the scrawlings of a Norman king. Yet they lie gathering dust in our national archives, hidden from view, forgotten. This is a guide to the Modern Domesdays.

1) Tithe maps (1830s-40s)

Since before the Norman Conquest, it had become customary for peasants to pay to the Church one-tenth of their produce, levied in kind. This continued, despite the Reformation, up until modern times. Then in 1836, the Tithe Commutation Act allowed tithes to be paid in cash rather than in goods. This necessitated the creation of accurate maps of all land, including who owned it and who occupied it.

Some of the tithe maps that were created made use of the earliest series of Ordnance Survey maps, drawn up during the Napoleonic Wars. Others were the first detailed maps of their area in existence. As a result, they varied in quality considerably. About 1,900 of the maps – one-sixth of the total drawn up – were ‘sealed’ by the Tithe Commissioners, denoting them to be very accurate. The rest were a mixed bag, ranging from half-decent maps to sketches. Even so, they remain valuable records, because of what accompanied them: Tithe Apportionments, ledgers setting out the owners and occupiers of each field and parcel of land. Today they reside in the National Archives; a few counties have digitised their tithe maps and put them online, but not many (e.g. Cheshire, East Sussex, Norfolk).

Tithe maps were, therefore, the first attempt since the original Domesday to survey the owners and occupiers of all land in England and Wales. Though to modern ears the concept of Church tithes sounds medieval, the appearance of the Tithe Maps in the 1840s were a sign of modernity: the replacement of feudal dues with the cash economy, the use of modern military cartographic methods to map out the lie of the land. Meanwhile, the Victorian state was taking an increasing interest in monitoring its burgeoning population through ten-yearly censuses, with the 1841 Census being the first to record the names of all individuals in a dwelling. This, unwittingly, was to sow the seeds for the second Domesday of modern times.

2) The Return of Owners of Land (1873-5)

The 1861 Census provoked a commotion amongst radicals, as its records seemed to show there were just 30,000 ‘owners of land’ in the whole country – though without revealing how much each owned.

The 15th Earl of Derby – himself a major landowner, and the son of the former Conservative Prime Minister – sought to disprove these claims. Addressing the House of Lords on 19th February 1872, he asked the Lord Privy Seal, “Whether it is the intention of Her Majesty’s Government to take any steps for ascertaining accurately the number of Proprietors of Land or Houses in the United Kingdom, with the quantity of land owned by each?”

An accurate survey would be a public service, Derby went on, for currently there was a “great outcry raised about what was called the monopoly of land, and, in support of that cry, the wildest and most reckless exaggerations and misstatements of fact were uttered as to the number of persons who were the actual owners of the soil.”

Viscount Halifax, responding for the Government, agreed, opining that “For statistical purposes, he thought that we ought to know the number of owners of land in the United Kingdom, and there would be no difficulty in obtaining this information.” (My emphasis.)

Above: The 15th Earl of Derby, left; Viscount Halifax, right.

Halifax duly tasked the Local Government Board with preparing a Return of Owners of Land. The Return was not produced by sending out surveyors, like the original Domesday, but by compiling and checking statistics already gathered on land and property ownership for the purposes of the Poor Law. This in itself was no mean feat: as is noted in the preface to the Return, “upwards of 300,000 separate applications had to be sent to the clerks in order to clear up questions in reference to duplicate entries”. No maps were made, but addresses were recorded.

The Return of Owners of Land was finally published, “after considerable but unavoidable delay”, in July 1875. (You can browse the c.1,000 pages of Vol 1 on Google Books, here). Its initial conclusions gave heart to the landed governing classes: there were, in fact, some 972,836 owners of land in England & Wales, outside of London. Yet 703,289 were owners of less than an acre, leaving 269,547 who owned an acre or above. Even this, the clerks pointed out, was likely an overestimate, based on county-level figures: anyone who owned land in multiple counties would be double-counted.

It fell to an author and country squire, John Bateman, to interpret and popularise the Return. In 1876 he published The Acre-Ocracy of England, in which he summarised the owners of 3,000 acres and above. It became a best-seller, going through four editions and updates, culminating in Bateman’s last work on the subject in 1883, The Great Land-Owners of Great Britain and Ireland. Bateman’s analysis confirmed the radicals’ worst fears: just 4,000 families owned over half the country. Meanwhile, 95% of the population owned nothing at all. The landed elite had been exposed.

Above: Bateman’s summary table from 1883 shows how the 4,217 Peers & Peeresses, Great Landowners and Squires owned 18 million acres – over half the recorded area of England & Wales.

Bateman’s books were intended to stimulate drawing-room conversation amongst the landed classes, but they also fanned the flames of social unrest. After all, this was an era when the right to vote could only be secured by owning property, something the Chartists had tried to overthrow (and, failing that, had sought to overcome by acquiring land themselves). It was a time when the working poor were squeezed into urban slums at the mercy of grasping landlords, their crowded tenements immortalised in the dark etchings of Gustave Dore and the writings of Charles Dickens. And it was a time of deep agricultural depression, with tenant farmers struggling to make ends meet in the face of a glut of cheap North American grain imports. Land reform had become the issue du jour.

And yet, land reform in Victorian England came to naught. As Kevin Cahill has described in Who Owns Britain, the Return of Owners of Land was rubbished and buried by the landowning establishment. And though English land reform became briefly an electoral issue – Joseph Chamberlain, for example, was elected in 1885 on the promise of ‘three acres and a cow‘ for all farmers – it soon faded. Whereas in Ireland, land reform became central to struggles for an independent Ireland, in England, the only substantive measure passed in the 19th century was the Allotments Act of 1887. It wasn’t until the start of the 20th century that interest in land reform in England and Wales revived.

3) Valuation Survey (1910-1915)

In 1906, the Liberals were swept to power in a landslide election victory, bringing to an end the Conservative hegemony that had dominated British politics since the 1880s. The ‘New Liberalism’ of the 20th century was committed to much greater state intervention than the laissez-faire policies of Victorian Liberals, including a greater willingness to introduce new taxes to pay for social welfare. One aspect of the New Liberalism was a fresh commitment to land reform.

By now land reform had won the support of two of the 20th century’s greatest statesmen: Lloyd George and Winston Churchill. Churchill, then a Liberal MP, wrote in his 1909 book The People’s Rights about the “evils of an unreformed and vicious land system”. Churchill, like radical economist Henry George before him, railed against “the landlord who happens to own a plot of land on the outskirts or at the centre of one of our great cities, who watches the busy population around him making the city larger, richer, more convenient, more famous every day, and all the while sits still and does nothing.” Churchill’s solution to this social evil, and that of the Liberal Government’s, was to introduce a form of Land Value Tax.

The Chancellor, Lloyd George, proposed a small Land Value Tax in the ‘People’s Budget’ of 1909, alongside hikes in income tax for the wealthy and a ‘super tax’ on the very richest. Unsurprisingly, these radical measures were vehemently opposed in the House of Lords, which remained stuffed with the landowning gentry. When the Lords duly voted down the Budget, sparking a constitutional crisis over which Chamber held the upper hand, the Government went to the country to obtain a fresh mandate. Returned to power with the support of Labour and Irish Nationalist MPs, the Liberals forced the People’s Budget through the Lords, and then passed the 1911 Parliament Act to constrain the Upper House.

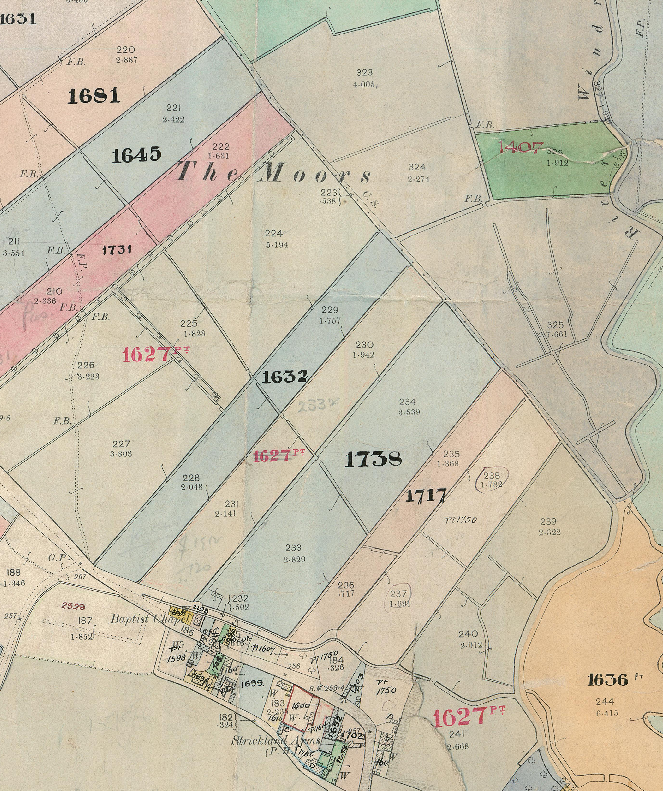

In order to levy the new tax on land values, current site values needed to be known, so a Valuation Survey was set up – dubbed at the time ‘Lloyd George’s Domesday’. The Valuation Survey took five years to draw up and involved the detailed mapping of land ownership across the country, using Ordnance Survey maps. Today, these maps, and their accompanying ‘domesday books’ listing owners and site values, are kept in the National Archives. Just one county, Oxfordshire, have made digitised versions available online.

Part of a Valuation Map for Oxfordshire.

The Valuation Survey and land value tax, however, came to a sorry end: interrupted by the outbreak of World War One, it was repealed in the 1920 Finance Act, under a government still led by Lloyd George but dominated by Conservatives. Though other efforts were made by future Labour governments to introduce forms of land value taxation, none came so close as Lloyd George.

4) National Farm Survey (1941)

The most recent of the Modern Domesdays had a rather different aim: it sought not to tax the rich, but ensure the country could feed itself in the face of total war. With shipping under assault from German U-boats and facing the threat of Nazi invasion, Britain embarked on ‘Dig for Victory’. The domestic side to this is well known: rationing, allotments, parks dug up for growing vegetables. Less appreciated today is the effort that went into identifying rural land that wasn’t being farmed, or that had fallen into disuse during the agricultural depressions of the late 19th century and interwar years.

To do so, Churchill’s war ministry mandated a National Farm Survey, overseen by the new War Agricultural Committees set up to direct farming. The initial survey was carried out in 1940-41, followed by a larger, two-year survey intended to inform postwar planning, and seen at the time as a ‘Second Domesday’ (disregarding the various other modern Domesdays!).

Though principally an investigation into land use, the National Farm Survey also interrogated ownership and tenancy. It covered all farms over 5 acres – around 320,000 farms in total – covering 99% of all agricultural land in England & Wales. However, as an academic paper on the 1941 Survey notes, although the “results were intended to be for use by planners and agricultural advisors, the original records were not made available for general inspection” until 1992. And while various historical studies have now been done using the National Farm Survey, the records remain on paper only, stored in the National Archives. A 2006 report made the case for digitisation of all the maps, but so far, no funder has been found.

Extract of a map from the 1941 National Farm Survey, showing farm ownership patterns.

Conclusion: Forgotten Domesdays

It seems extraordinary that these four, gigantic surveys of who owns England and Wales should have been so quickly forgotten. For sure, the immediate reasons for their creation – the levying of taxes by Church and State, the need to feed Britain in a time of war, the threat of popular uprisings against a landowning elite – have faded into history. But it’s still remarkably convenient for England’s landowners that all these Modern Domesdays have been left to gather dust in our archives, and that none have been properly digitised.

Of course, today’s landowners would claim that these surveys bear scant relevance to recent patterns of landownership. But knowing how many aristocratic families have retained their grip on the land down the centuries, I’m not so sure. In a future blog post, I hope to illustrate how land ownership has changed hands – or remained the same – over time by profiling a landed estate through these four different Modern Domesday surveys, together with current Land Registry records.

The Land Registry has recently said it will finally complete its register of land ownership by 2030. But without a means of compelling owners to register land, it’s going to struggle. Perhaps it’s time to speed things up, with a true Modern Domesday.

Thank you Guy. This is really interesting!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Excellent work. We have Andy Wightman in Scotland working on gaining transparency in Scottish land issues. Hope you can shed light on the subject for England and Wales.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on sideshowtog.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great article – succinct and lucid analysis of the current situation.

However, I think that in the interests of currency a slight amendment/ update might be in order. Tithe maps, as you say, have languished in archives for decades and only a few of the (richer?) counties have managed to find the resources to digitise them. BUT a commercial service, The Genealogist, now offers online access to what it implies (but never explicitly states) is a comprehensive collection of both maps and accompanying tithe apportionments. The down side is that access requires payment of their “diamond” subscription, currently £120 p.a. The further down side is likely to be (just a guess) that they have done a deal with the owners of the originals to forestall any future digitisation that might undermine their making a return on their investment. So, the original data is free and in the public domain, but the images and indexes have a jealously guarded copyright.

Now you may be able to persuade the company that as a highly respected academic and journalist it would be advantageous for them to grant you free access, or that granting your charity free access would count as a contribution in kind, but for all but the most dedicated this looks like a very expensive option..

Genealogist tithe records (https://www.thegenealogist.co.uk/)

Interestingly, the registered address for the company is

Genealogy Supplies (Jersey) Ltd, PO Box 530, Jersey JE4 8XX

Which reminds me of something you may or may not already be aware of – Private Eye’s investigation into foreign ownership of UK property. The results are freely downloadable as a spreadsheet.

Selling England (and Wales) by the pound (http://private-eye.co.uk/registry)

Overseas ownership spreadsheet (http://www.private-eye.co.uk/pictures/extra/overseas-company-dataset-december-2014.xlsb)

LikeLike

Well written. I’ve published a book about the acquisition of property by one family of landowners over half a millennium and the effects of Govt policy in the 19th century – namely Lloyd George’s ‘Peoples Budget’. Inheriting the Earth: The Long Family’s 500 Year Reign in Wiltshire is available on Amazon, if you’re interested. In 1872 the results of a parliamentary enquiry into land ownership showed the Longs’ Wiltshire estates were in the top ten, just behind the Earl of Pembroke, the Marquess of Ailsbury and the Marquess of Bath, covering about twenty-three percent of the entire area of the county. The Longs were the first to start the avalanche of selling off their agricultural land to avoid the tax, mostly to sitting tenants.

LikeLike

Thanks! That sounds fascinating – I’ll check it out!

LikeLike