Photo: 11th Duke of Devonshire by Allan Warren, own work, CC BY-SA 3.0

Dukes are the highest-ranking tier of the British aristocracy – a select elite within an elite, ranking above Marquesses, Earls, Barons and Viscounts, whose lands and titles derive from centuries of Royal patronage.

There are 30 Dukes in the UK today. Five of these are ceremonial titles for members of the Royal family, conferring no wealth or estates. The one other Royal Duke who is a significant landowner is Prince Charles, Duke of Cornwall, whose 135,000-acre estate I’ve written about elsewhere.

The remaining 24 Dukes are all extremely wealthy men who together own around a million acres of land. Yet my investigations show that the taxpayer continues to subsidise them to the tune of £8million annually, through our broken farm subsidy system. What’s more, many of the Dukes benefit from tax breaks on their wealth and have constructed elaborate trust fund schemes to avoid inheritance taxes. How the Dukes have survived and prospered into the 21st century is a telling insight into modern English society.

The Dukes’ landholdings and subsidies

Britain’s Dukes are some of the largest private landowners in the country. The Duke of Buccleuch, for example, owns some 270,700 acres across England and Scotland – twice the area owned by the Prince of Wales, and about half the size of Greater London. The Duke of Westminster, who I’ve written about previously, owns a large grouse moor in Lancashire, extensive farmlands in Cheshire, and prime real estate in central London. Many of the Dukes regularly feature in the Sunday Times Rich List as multimillionaire owners of stately homes, property, land, and historic artworks.

They are also, I can reveal, the recipients of generous taxpayer handouts. Thanks to the broken system of farm subsidies under the EU Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), 17 of the UK’s 24 non-Royal Dukes receive large annual farm subsidies for the lands they own. In 2015, these summed to £8.4million, paid to the Dukes directly or to trusts, companies and entities controlled by them.

I reached this figure by researching the Dukes’ landholdings and company directorships, and searching DEFRA’s CAP payments register to identify what each received. Over half of the taxpayer-funded subsidy was in the form of ‘single area payments‘, calculated by land area – that is to say, payment simply for the privilege of owning land, rather than for growing food or performing an environmental or social service (beyond the basics of cross-compliance). The table below summarises my findings; this Google Spreadsheet provides the full sources.

| Title | Land (acres) | Farm subsidies*** | ||

| 1873* | 2001** | Total 2015 | Single area payments | |

| Duke of Buccleuch and Queensberry | 460,108 | 270,700 | £1,643,510 | £707,036 |

| Duke of Grafton | 25,773 | 11,000 | £835,559 | £495,320 |

| Duke of Westminster | 19,749 | 129,300 | £815,805 | £462,775 |

| Duke of Devonshire | 198,572 | 73,000 | £768,623 | £218,856 |

| Duke of Beaufort | 51,085 | 52,000 | £688,097 | £345,075 |

| Duke of Bedford | 86,335 | 23,020 | £543,233 | £431,163 |

| Duke of Marlborough | 23,511 | 11,500 | £526,549 | £284,468 |

| Duke of Norfolk | 49,866 | 46,000 | £449,166 | £259,605 |

| Duke of Richmond, Lennox, and Gordon | 286,411 | 12,000 | £379,085 | £253,038 |

| Duke of Roxburghe | 60,418 | 65,600 | £361,919 | £175,938 |

| Duke of Rutland | 70,137 | 26,000 | £358,430 | £314,531 |

| Duke of Northumberland | 186,397 | 132,200 | £327,403 | £133,553 |

| Duke of Sutherland | 1,358,545 | 12,000 | £191,802 | £170,419 |

| Duke of Atholl | 201,640 | 148,000 | £172,436 | £60,287 |

| Duke of Fife | (Title didn’t exist) | 1500 | £169,905 | £144,364 |

| Duke of Argyll | 175,114 | 60,800 | £120,097 | £0 |

| Duke of Wellington | 19,116 | 31,700 | £80,878 | £66,486 |

| Duke of Montrose | 103,447 | 8,800 | N/a | N/a |

| Duke of Somerset | 25,387 | 2,000 | N/a | N/a |

| Duke of Hamilton | 157,368 | 12,000 | N/a | N/a |

| Duke of Abercorn | 78,662 | 15,000 | N/a | N/a |

| Duke of St Albans | 8,998 | 4,000 | N/a | N/a |

| Duke of Manchester | 27,312 | 0 | N/a | N/a |

| Duke of Leinster | 73,100 | 0 | N/a | N/a |

| Totals | 3,747,051 | 1,148,120 | £8,432,497 | £4,522,914 |

*1873 landholdings are from the Return of Owners of Land. **2001 acreages taken from Kevin Cahill, Who Owns Britain. ***Farm subsidy figures are all from Defra’s 2015 CAP subsidy register. This Google Spreadsheet explains the different trusts, companies and entities that received the subsidy, and their relationship to each Duke.

Men of broad acres

I’ve mapped the stately homes that form the family seats for Britain’s Dukes, alongside what I can find on their wider landed estates, in the map below. The polygons (visible when you zoom in) are drawn from Environmental Stewardship maps published by Natural England or, in the case of the Berry Pomeroy estate owned by the Duke of Somerset, a landowner deposit map released as a GIS file by Devon Council under FOI and recorded by them under the Highways Act 1980, section 31.6. The latter should show the Duke’s whole estate (in Devon, at least); Environmental Stewardship maps won’t show the full acreage owned by each Duke, just those portions of his land for which he’s claiming such subsidies.

Conservation writer Miles King has also uncovered another very useful source of maps showing many aristocratic estates: HMRC’s maps of heritage properties exempted from Inheritance and Capital Gains Tax. These detail around 350 stately homes and estates that have had tax waived on them in return for opening their doors and art collections to the public. In terms of Ducal estates, HMRC’s maps reveal:

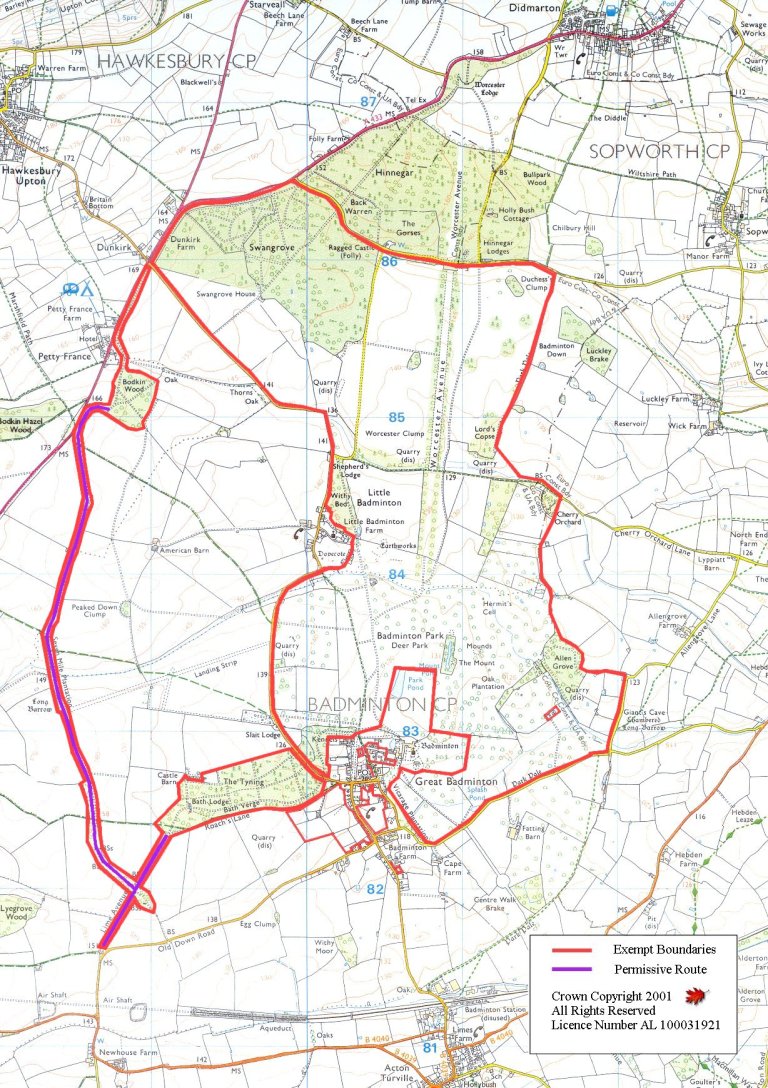

The Duke of Beaufort’s estate at Badminton:

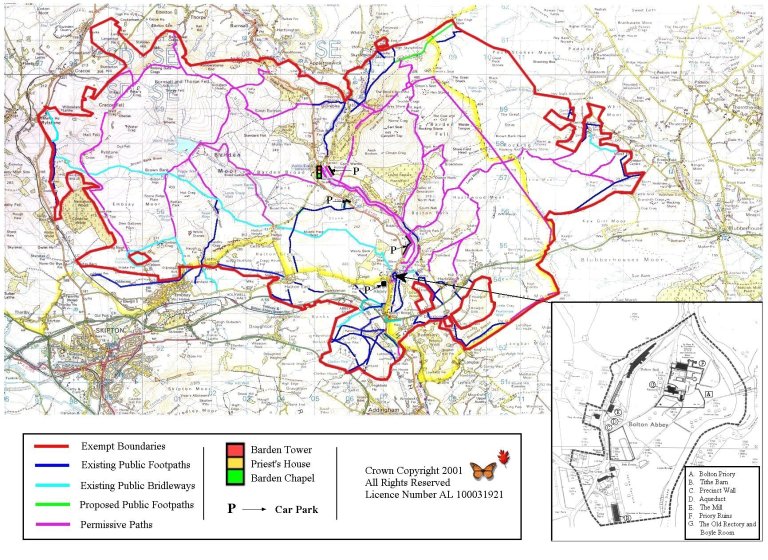

The Duke of Devonshire’s grouse moors at Bolton Abbey in Yorkshire (he also owns Chatsworth House and its estate in Derbyshire, marked on the Google Map above using polygons derived from Environmental Stewardship maps):

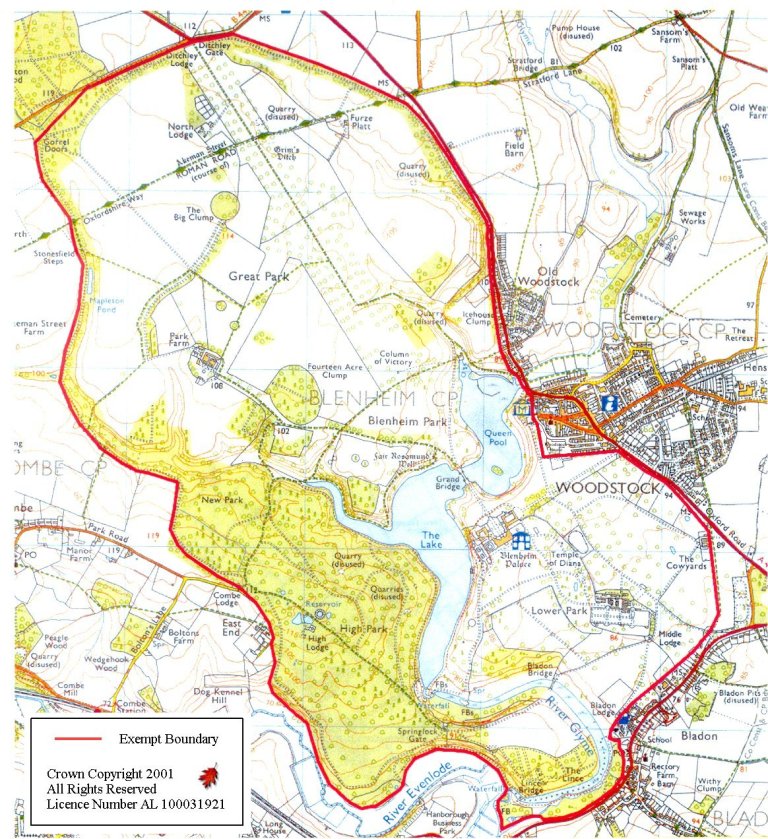

The Duke of Marlborough’s estate at Blenheim Palace in Oxfordshire:

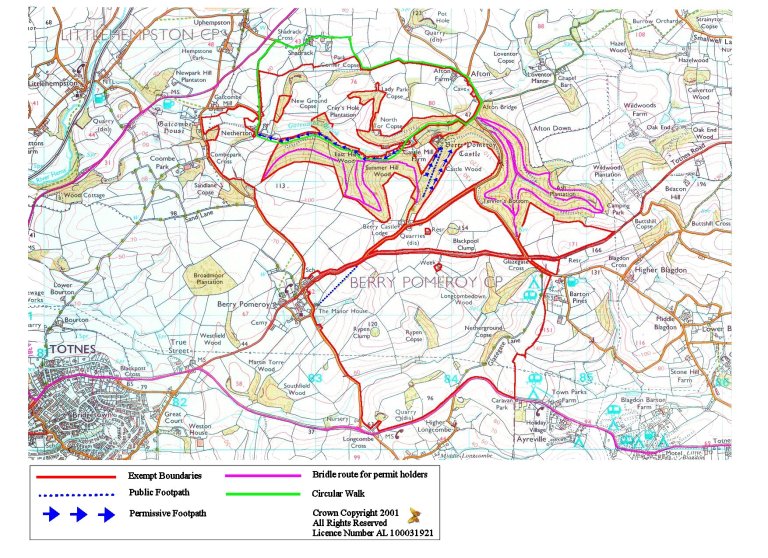

And the Duke of Somerset’s lands at Berry Pomeroy in Devon:

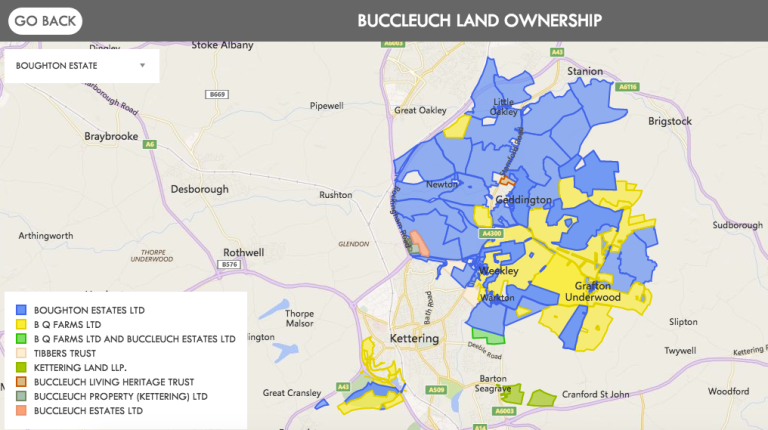

Lastly, a final source of maps: the Duke of Buccleuch’s estates have now published online maps themselves, spurred on no doubt by the efforts of Scottish land reformers like Andy Wightman. This one below shows their Boughton Estate in central England:

Tax breaks and inheritance trusts

As if owning a million acres and reaping £8million of farm subsidies wasn’t enough, the Dukes also benefit from a number of tax breaks and wheezes. As mentioned above, various Dukes take advantage of HMRC’s waiver on Inheritance and Capital Gains tax by throwing open their doors and letting in the great unwashed. Fifty years ago, under more punitive taxation regimes, aristocrats were scrabbling about to find additional sources of income; the Duke of Bedford was one of the pioneers with the business acumen to set up Woburn Safari Park in his sprawling estate. Nowadays, the cult of the stately home sustains many of the Peerage.

Britain’s Dukes are also now past masters at wangling inheritance tax dodges. As Kevin Cahill notes in Who Owns Britain, “Almost without exception, all the [Ducal] land identified is in trust”. To have land and wealth vested in a Trust means that you don’t own it directly, but you – and your descendants – are its beneficiaries, with the Trust administered by Trustees. This can be advantageous for the passing on of inherited wealth without incurring Inheritance Tax. That’s how the young 7th Duke of Westminster avoided paying 40% tax on his £9bn inheritance following the death of his father last year.

Trusts can also help conceal their ultimate beneficiaries from the public eye. For example, a grouse moor at Abbeystead in the Forest of Bowland is registered in the name of three trustees (or possibly directors) of the Grosvenor Estate, whose ultimate beneficiary is the Duke of Westminster – but whose name doesn’t appear on the title deed. Nor are Trusts considered corporate entities by the Land Registry, so they refuse to disclose what land they own (whether via PN1 searches or by bulk dataset downloads), citing Data Protection concerns. And there is no public register of Trusts – unlike for companies, which must register with Companies House, or charities, which must be registered with the Charity Commission.

The decline, fall… and survival of the English aristocracy

“The greatest trick the devil ever pulled was convincing the world he didn’t exist” – Roger ‘Verbal’ Kint in The Usual Suspects

Even without the cloak of concealment afforded by Trusts, Britain’s Dukes today have the advantage that few are even aware of their still-vast wealth and landholdings. There is a widespread perception that the aristocracy are dead.

This perception owes much to the work of the historian FML Thompson in his 1963 work English Landed Society in the Nineteenth Century, popularised and embroidered in David Cannadine’s brilliant book The Decline and Fall of the British Aristocracy (1990). Both Thompson and Cannadine argue that the Dukes (like the aristocracy at large) were at the pinnacle of their power in the mid-Victorian period, owning nearly 4 million acres of estates at the time of the 1873 Return of Owners of Land. But, they declare, between the 1880s and 1920s the entire aristocratic class experienced a catastrophic loss of territory, wealth and political power – plagued by death duties, assaulted by land reformers and Lords reform, and losing out to the nouveau riche.

No-one seriously disputes that the British aristocracy fell from grace after their Victorian heyday, but the extent of that fall seems to have been exaggerated – particularly when it comes to their landholdings. Thompson and Cannadine’s claims in fact come down to one, rather shaky source. Cannadine says that “In the years immediately before and after the First World War, some six to eight million acres, one-quarter of the land of England, was sold by gentry and grandees”. Thompson likewise asserts “it is possible that in the four years of intense activity between 1918 and 1921 something between six and eight million acres changed hands in England.” For this startling figure, both relied on a single article in a single edition of the property magazine Estates Gazette from December 1921.

This figure has recently been challenged, convincingly, by John Beckett and Michael Turner in the academic journal Agricultural History Review. The authors examine land sales data from the 1890s through to the 1920s and find that “much less than 25 per cent of England changed hands in the four highlighted years 1918-1921”, concluding that actually it was more like 6.5%, and that the Estates Gazette had massively overstated the case in a fit of panic.

What may have felt seismic at the time also looks a deal less drastic in retrospect. In 1978, a century after the Return of Owners of Land, the Marxist geographer Doreen Massey was still able to show that ‘Great Landed Estates’ likely owned around 31.6% of Great Britain. And Kevin Cahill’s 2001 calculations that Britain’s Dukes still own over a million acres between them show that, whilst they have experienced relative decline, the Dukes are still huge landowners.

What’s more, a closer reading of Thompson and Cannadine reveals a quiet admission that the highest echelons of the aristocracy – the Dukes – have been able to cling on to their landed estates with much greater success than the lesser nobles and gentry; and that England has avoided the land reforms enacted in Ireland and started in Scotland. As Thompson states in the final pages of his book: “The landed aristocracy has survived with far fewer casualties [than the lesser gentry]… Among the great ducal seats, for example… Badminton, Woburn, Chatsworth, Euston Hall, Blenheim Palace, Arundel Castle, Alnwick Castle, Albury and Syon House, Goodwood, Belvoir Castle, Berry Pomeroy, and Strathfield Saye are all lived in by the descendants of their nineteenth-century owners.” That Thompson could say this half a century after his supposed ‘revolution in landownership’ is startling enough. Even more startling then that today, another half-century on, every single one of those Ducal family seats still remains in the hands of the same aristocratic families.

In other words, the Dukes have pulled off their greatest trick. Propped up by tax breaks, the clever use of trusts and our current system of farm subsidies, they have found a way to thrive in obscurity. As the late, great Terry Pratchett put it in one of his satirical Discworld novels, summarising the fortunes of the aristocratic Rust family: “The Rusts had adapted well… [by] doing what aristocrats have always done, which is trim sails and survive.”

Oxfordshires landowner deposits pages have a map of the Blenheim estate.as to the figure of 52,000 acres for the Beaufort estate I’ve long been dubious about this .it’s well documented the large welsh estate was sold in the late 19th early 20th centuries leaving only manorial lordship rights in Gower.as for the rest, the national archives page on the family papers it holds states that the glos/wilts estate was 11,000 acres in 1948.

LikeLike

further to the above-magic has details of swan grove farms the Beaufort farming operation.the figure for the Norfolk estate may or may not be correct I don’t know.but in the fifties the then 16th duke acquired an act of parliament to disentail the family estates.he had only daughters and on his death 8,000 acres in Sussex was left to them.this is the angmering estate.one daughter lady Mary herries inherited the caerlaverock estate in Scotland which she still owns and everingham in Yorkshire which was sold.the 17th duke had an inheritance from his mother the 13 lady Beaumont comprising Carlton towers near goole and urban property in the nw.carlton towers is about 2,000 acres.the 17th duke also bought the arkengarthdale moor estate from the heirs of the aircraft pioneer Tommy sopwith.finally the family portfolio includes freeholds in the strand,sheffield commercial and residential assets and the motte of clun castle and possibly some residual scraps at kenning hall and the lophams in Norfolk.

according to the estate website the northumberland estate is 100,000 acres. I assume this may exclude the Scottish burnside moor estate, lord James percies linhope estate, the small property at syon and the estate at Albury in surrey(for which see Surrey cc’s landowner deposits).hope this is useful

LikeLike

Hi Steve, huge thanks, this is all fantastically helpful! I’ll try to follow up on those estates ASAP and see if more maps are available (like as you say under council landowner deposits) and update the blog as and when I do. Thanks!:)

LikeLike

pleased to discover just tonight that Lancashire county council has a mapping site called Mario (maps and related information online) .it shows landowner deposits and has the duke of Westminsters abbey stead estate, the earl of Derbys estate and a large church of England estate.

LikeLike

Amazing! Just had a look at it – looks great, will add it to my Highways Act blog / database. Thanks Steve! 🙂

LikeLike

This is all fantastically useful and well researched. Every effort must be made to bring it into mainstream politics now. Guy Standing

LikeLike

This is all very well, but I am afraid that the socialists cannot have it all one way. Large acreages and large subsidies enable conservation to take place. If capping were to be introduced how long would it be before houses fell into disrepair, or worse as was seen after the second world war when the Attlee government taxed the aristocracy. What may not be fair is how the Dukes were awarded their acres in the first place, but as things currently stand I can see nothing wrong at all in trying to preserve an inheritance. Wouldn’t you?

LikeLike

Preserving inheritance at the expense of taxpayers is not acceptable. Do it with your own monies.

LikeLike