This blog post is by Guy Shrubsole. Image: hazel grove, Devon.

Land ownership in Britain is highly concentrated and unequal: just 1% of the population own half the land in England, while in Scotland just 432 landowners own 50% of the private land. This isn’t only an issue of social and economic inequality; it also poses major problems for transforming the way we use land in order to address the climate and nature crises.

That’s because owning certain types of land also means effectively owning natural carbon sinks. Peat soils, for example, constitute England’s single largest carbon store, covering about 1.7 million acres and storing over half a billion tonnes of carbon. Most of this vast carbon sink belongs to just a handful of landowners – about a million acres of peat is owned by just 124 individuals and organisations. Yet because of the way these landowners mismanage this carbon sink – setting fire to it for grouse shooting and keeping it drained for lowland agriculture – it’s become badly degraded. Peat soils in England now leak 11 million tonnes of CO2e into the atmosphere each year.

So what can be done?

1. Pay existing landowners to manage their land better

One obvious solution to this problem is to incentivise existing landowners to manage their land for nature and climate. That’s been the main focus of the current Conservative Government, with their post-Brexit reforms to farm subsidies – replacing the old EU Basic Payments Scheme (which essentially rewarded landowners for the area of land they owned) with a system of Environmental Land Management schemes, paying ‘public money for public goods’.

But the Government states that ELMs will only restore “up to 300,000 hectares [740,000 acres] of wildlife habitat by 2042”, translating to just 37,000 acres per year over the next two decades – a drop in the ocean given that England is 32 million acres. Even if these payments were increased and directed more effectively, it’s questionable whether an essentially voluntary, incentive-led approach will fundamentally shift destructive land use practices in the areas where this is most needed. Most of the owners of England’s upland peat, for example, are wealthy men and women who aren’t short of cash – and who own their grouse moors as ‘trophy assets’ for social cachet rather than as purchases that make much economic sense.

2. Buy up land on the open market and give it back to nature

Another much-vaunted solution is for conservationists to simply buy up land, and give it back to nature – whether through rewilding or other approaches to ecological restoration. This, after all, is the approach taken traditionally by conservation and heritage charities, starting with the National Trust acquiring commons and stately homes from the late 19th century, through to the RSPB, Woodland Trust and others purchasing land to protect as nature reserves. Together, conservation charities now own around 2% of England. In more recent years, they’ve been joined by private investors and crowdfunded trusts, motivated by a combination of goodwill and the desire to profit from new revenue streams like reformed farm payments and emerging carbon offset markets. There’s also increasing scope for communities to get involved in land purchase, via Community Right to Buy laws – something that’s existed in Scotland for the past twenty years, and which the Labour party have recently pledged to introduce in England.

But there’s a problem. There simply isn’t enough land being sold each year for land purchase to be the ‘silver bullet’ solution to the climate and nature crises.

As land agents Savills say: “Farmland is held for a long time, with average turnover rates estimated at once in every 200 years”. Their latest statistics show that just 122,400 acres of land in Britain was publicly marketed in 2021, a near-record low. But this isn’t just a short-term blip; the amount of land coming to market has either fallen or stagnated since Savills started monitoring it in 1992. Over the last decade, an average of just 150,000 acres of land in Britain has come to market.

Britain – England, Wales and Scotland – is roughly 57 million acres in size (adding in Northern Ireland takes the total to around 60 million acres). The 150,000 acres of land publicly sold each year therefore amounts to just 0.3% of Britain. At this rate of sale, it would take a century for new market entrants to buy up 30% of Britain’s land to protect it for nature and climate reasons – the area of land pledged by the Government under its ‘30×30’ commitment.

Even this underestimates the problem. The vast majority of farmland sales are of small farms. Savills’ data shows that estates of over 1,000 acres make up on average only 1% of publicly marketed sales, with over three-quarters being farms of under 250 acres. Big grouse moor estates come onto the market once in a blue moon. Nor is there necessarily any pattern to where land will come up for sale – it’s rare to find several neighbouring blocks of land coming to market simultaneously.

Whilst it’s possible to restore elements of nature to even the smallest patch of land, having tiny islands of biodiversity in a sea of nature-depleted farmland isn’t that helpful. It is, after all, what’s been tried for over a century, and it’s not working to halt the precipitous decline in biodiversity. What’s really needed is larger areas of land in which nature can regenerate and natural processes be restored, and for these ‘refugia’ to be better connected through wildlife corridors running throughout the landscape. The scientist Sir John Lawton articulated this best in his seminal 2010 report calling for nature reserves to become ‘bigger, better, more and joined up’.

So if we can’t rely on the ‘free market’ to bring forward enough land, what else can be done?

3. Speed up the market sales process by using compulsory purchase

One way to speed up land purchase would be for public bodies to make greater use of compulsory purchase powers (called Compulsory Purchase Orders, or CPOs). Currently, government bodies and councils have the ability to force the sale of land that’s deemed to be vital for the ‘public interest’. But this power tends to be used very sparingly, and often in ways arguably detrimental to nature: for large infrastructure projects like HS2, for example, which has ploughed its way through lots of ancient woodlands.

Local authorities, meanwhile, are wary of using CPOs to buy up land even to build new affordable housing – such are the costs of compensating existing landowners (and risks of legal challenges). The Government is currently consulting on changes to land compensation rules which could alleviate some of these costs, but even reformed CPO powers are likely to be used mainly for housing projects – not for buying land to leave it for nature or restore carbon sinks.

There are two public bodies in England, however, that have both compulsory purchase powers and an interest in acquiring land for reasons other than development. They are the Forestry Commission and Natural England. When it was first set up over a century ago, the Forestry Commission acquired tens of thousands of acres of land (both on the open market and via compulsory purchase) to plant up for forestry. Natural England’s predecessor bodies were empowered by the National Parks & Access to the Countryside Act 1949 to use CPOs to acquire and set up National Nature Reserves.

Yet neither body has used their CPO powers for significant purchases for decades. Natural England’s budgets have been hit hard by austerity over the past twelve years, whilst the Forestry Commission has swallowed some of the small-state ideology of successive Conservative administrations who have threatened to privatise and sell off the public forest estate. Nor does the Forestry Commission have a great track record of promoting biodiversity: the vast majority of its landholdings comprise monoculture pine plantations, many of which were established on former ancient woodlands, cut down to make way for fast-growing timber.

But if the Government wanted to change this, it could. The Forestry Commission ought to be given a new statutory duty to promote nature recovery and help reach net zero – proposals in fact hinted at in DEFRA’s recent Nature Recovery Green Paper. And Natural England needs to be far better funded, so that it has the budgets to acquire new National Nature Reserves as it sees fit.

Even so, buying land – whether on the open market or via compulsory purchase – remains an expensive option. The average price of farmland across Britain is currently roughly £7,500 per acre. That means that:

- To buy up all the 150,000 acres of land publicly marketed annually would cost around £1.13 billion per year.

- To speed up the supply, by compulsorily purchasing sufficient land to reach 30% of Britain by 2030, let’s say starting in 2025, you’d have to invest roughly £25.6bn per year (30% of Britain’s 57m acres is 17.1m acres, divided by 5 years = 3.42m acres per year, x £7,500/acre).

- Or, if we focus on doing this in England only, you’d need to invest around £14.4bn per year (30% of England’s 32m acres is 9.6m acres, divided by 5 years = 1.92m acres per year, x £7,500/acre).

- Compulsorily purchasing the 1.7m acres of peat soils in England is a little more affordable: if the Government sought to do this over a five-year period, it could cost around £2.5bn per year (1.7m acres x £7,500/acre, divided by 5 years).

But there is also a fourth approach…

4. Better regulate how land is used – via a Land Use Framework, more powers for National Park Authorities and other policies

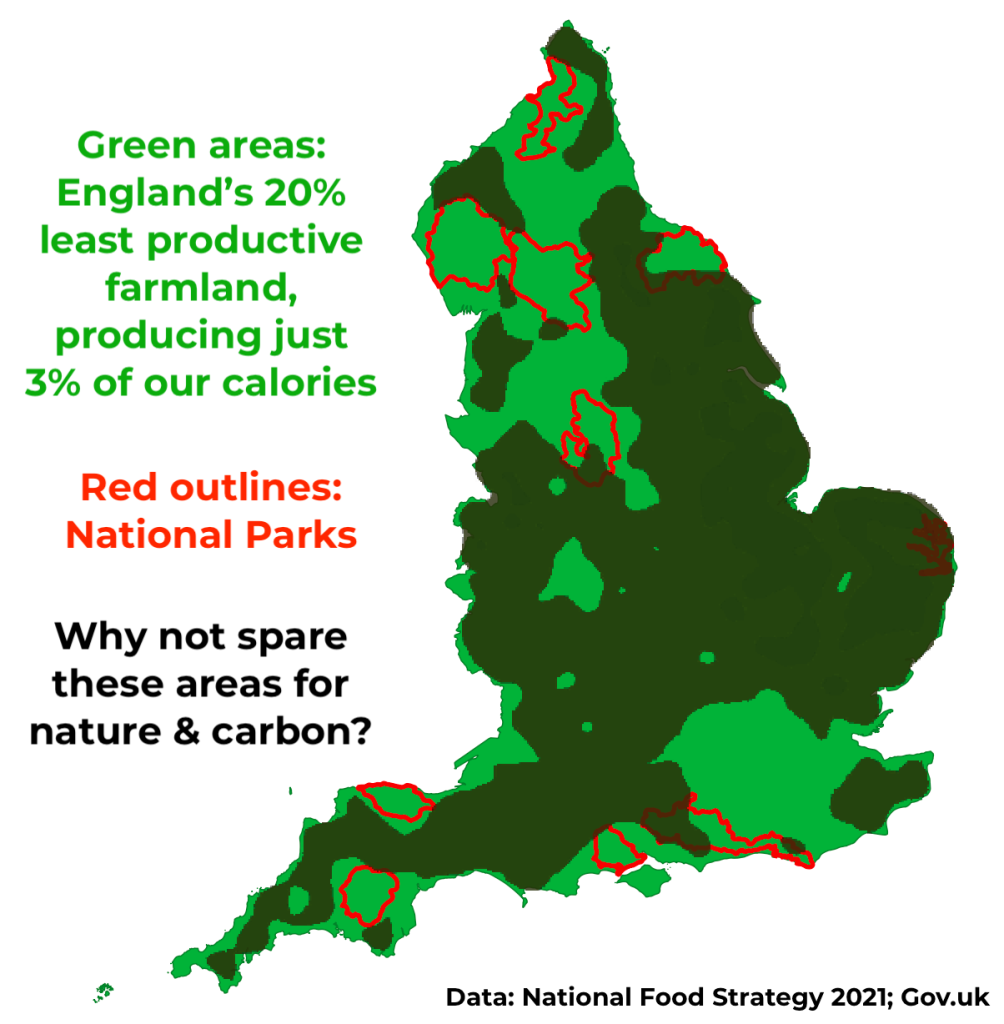

In addition to paying existing landowners, and investing capital budgets in purchasing land outright, the use of land should also be better regulated. It should be subject to an overarching Land Use Framework, setting out how land is best used, and making clear that land which is least productive for growing food – the 20% of England that generates only 3% of our calories, mostly upland areas where we also find much of our carbon-rich peat – should be prioritised for nature restoration and carbon sequestration.

National Park Authorities and AONBs should also be given new powers to direct land use in these areas, and much more of England should be designated as Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSIs), giving Natural England the power to monitor and intervene where the health of these habitats is deteriorating.

Lastly, the Government could vest the ownership of biological carbon in the Crown, recognising it as a strategic national asset. The 150 or so landowners who own England’s largest carbon store – our peat soils – would still own the freehold to the land, but not the carbon it contains: it would be Crown property. If those landowners chose to manage their land in such a way as it added to the national carbon stock – such as by re-wetting peat bogs and allowing trees to naturally regenerate – they should be rewarded for this. But if landowners continued to damage our national carbon stock, the Crown could take legal action against them for infringement of its newfound property rights.

Such is the urgency and scale of the climate and nature crises, we should really be using a combination of all four of these approaches. Reformed farm payments to existing landowners, more purchase of land for nature via the open market, greater use of compulsory purchase powers by public nature bodies, and stronger regulation of how land is used – all of these are needed if we’re to restore habitats and natural carbon sinks at scale. Tinkering around the edges is no longer an option.

That idea sounds great. If we zoned land for best agricultural land/infrastructure/housing/nature recovery then the value of the land for nature recovery so it can’t be used for anything else could well fall meaning that it would be cheaper to buy up. Or am I being naive?

LikeLike

Very interesting article, it make a lot of sense. Could something be done with inheritance rules, maybe land over a certain amount should become the property of the state on the death of the owner, with a lease-back facility to keep farms intact. If land wasn’t owned but leased the mindset might change to that of custodians during our brief spell on this earth.

LikeLike

It has always seemed to me to be odd that agricultural land isnt subject to the sort of restrictions that apply to most other sorts of land so that you can no more burn a prat bog for grouse shooting that I can convert my house into a night club

LikeLike

Hi Guy, this isn’t actually true…

When it was first set up over a century ago, the Forestry Commission acquired tens of thousands of acres of land (both on the open market and via compulsory purchase) to plant up for forestry.

Although the FC does have powers to compulsory purchase land it has never happened. There was a case in the 1950’s in the Upper Twyi valley where there was a compulsory purchased proposed but there was an appeal and with significant protesting it never happened.

BTW really enjoyed your temperate rainforest book

LikeLike

Another excellent article. Thanks.

LikeLike